Dive 121: Why modern apologies feel so hollow

What we lost when “sorry” became cheap

Hey, it’s Alvin!

I was riding the train the other day when an onboard announcement made me realize something I didn’t expect…

We no longer know what an apology is for.

And the reason it matters is that understanding what an apology is for is vital for a good life, healthy relationships and even a healthy, robust society. You can tell someone doesn’t understand apologies if they say something like, “an apology is the first step towards making amends.”

There is a children’s song literally called, “Saying I’m Sorry is the First Step.”

There’s a Psychology Today article that tells you to “First, begin with a sincere expression of regret.”

There’s even a Harvard Medical School blurb that says, “An apology can often be the first step to better understanding in a damaged relationship.”

Except…

An apology is not the first step towards making amends.

It’s also not the last. But we’ll get to that later.

An apology might be the first visible step. But morally, it sits in the middle of all that matters. When people spend their whole lives with a flawed understanding of apologies, you get the corporate nonsense I experienced on my train ride…

The Train of Apologies

I’m riding on a Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway train. Steel wheels on polished rails, speeding below city streets at a brisk 60 km/h (~37 mph) towards the bustling downtown financial district. Suddenly, we slowed down. To a snail’s pace. An automated announcement comes on in a robotic monotone:

“Attention passengers: this train is delayed due to track work ahead. The TTC apologizes for this inconvenience.”

After a few minutes that feel like an eternity, the train speeds back up to 60 km/h, relieved that I might just get to my destination on time as I peer out the window, watching the tunnel lights tick by at the rhythm of the train. Suddenly, my upper body bows forward. As the train brakes. Again.

“Attention passengers: this train is delayed due to track work ahead. The TTC apologizes for this inconvenience.”

A few more minutes pass. My heart starts to race. Will I make my appointment on time? The train picks up speed again, stopping at stations as expected, but otherwise moving at a quick clip, barrelling down the tunnel like a meteor eager to arrive at the Earth’s surface. Standing passengers stumble as the train brakes. Oh no. Not again.

“Attention passengers: this train is delayed due to track work ahead. The TTC apologizes for this inconvenience.”

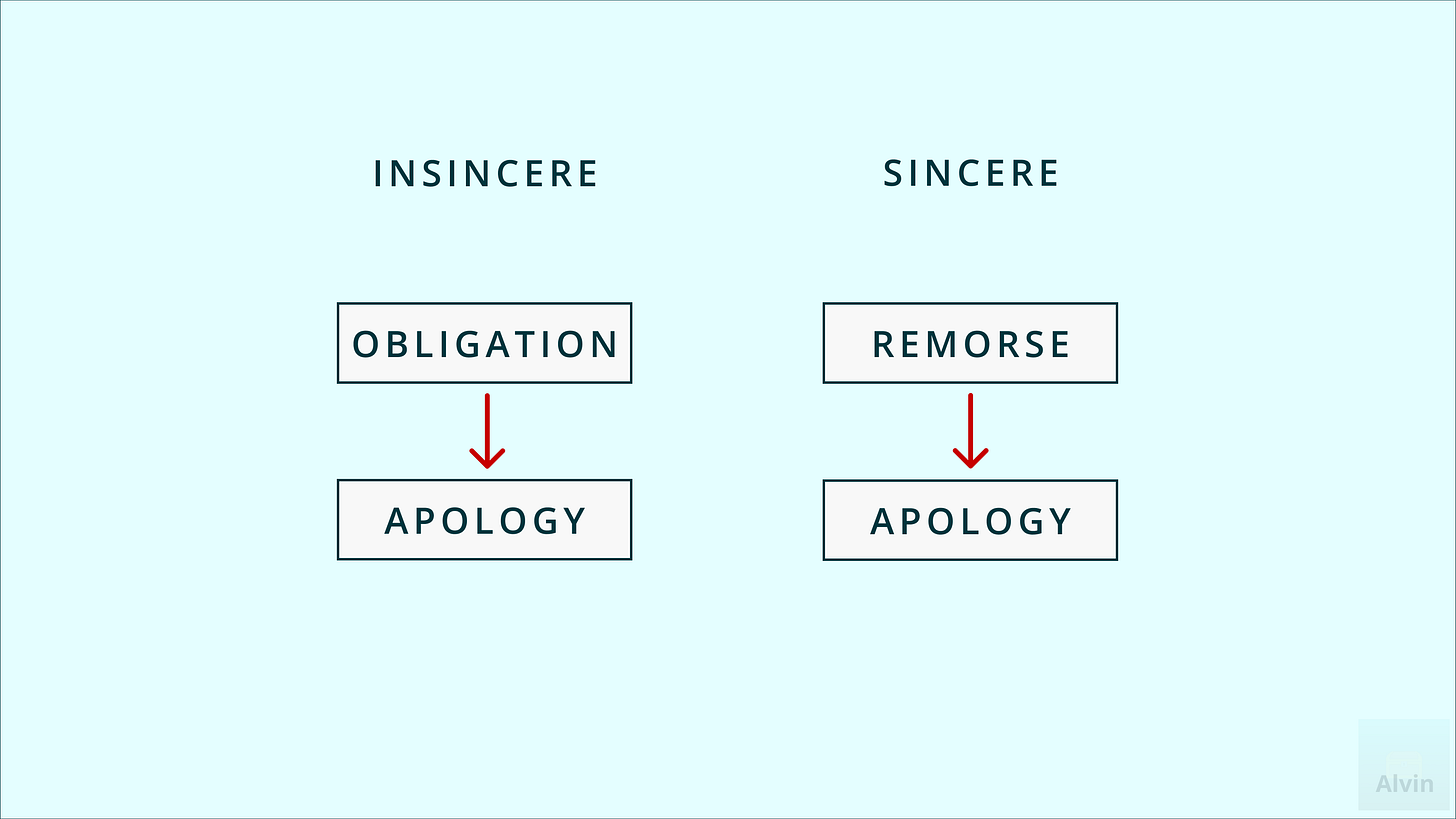

I don’t know anyone who takes these apologies seriously. They feel too hollow. Why? They’re missing two key ingredients: remorse and repair.

The Purpose of Apologies

When I was a kid, the adults in my life taught me and other kids that if you did something wrong, just say you’re “sorry,” and that was pretty much it.

For the youngest children, that makes perfect sense because they haven’t yet developed abstract moral reasoning. And a typical infant can’t grasp how another person feels. They lack a theory of mind. So, they’re taught the behaviour first (i.e. “say you’re sorry”).

As kids mature, they learn that sometimes their actions hurt others, which leads to remorse. It’s then that most kids learn that an apology is just an acknowledgement to another that they feel bad for what they did, and they want to make up for it to repair the relationship.

But remorse often takes effort. You don’t have to feel bad for what you did if you rationalize it away or just don’t think about it. You have to choose to reflect on your actions and their impact on another for remorse to emerge. But because self-reflection is less publicly visible, it’s a step we often ignore.

Modern culture treats the first visible step as if it were the first meaningful one.

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

― Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

A willingness to repair the relationship with action is also vital. A politician might apologize for the poor public transit service, but if they do nothing to change it, then the apology is just as meaningless. So, really, the whole proper process is:

Recognition

Acknowledgment (or Apology)

Repair

So, the first step is not the apology; it’s the recognition of wrongdoing, which often requires conscious reflection.

This also explains why the train announcements often ring hollow. And that’s just as true of other corporate and political apologies. Neither the transit agency nor the computerized systems making the automated apologies can reflect or feel remorse. The apologies are extra insulting if the transit agency doesn’t take meaningful steps to improve service. Everyone knows these apologies are pointless, so why are they made at all?

The Perversion of Apologies

Apologies are emphasized in modern institutions not because they lead to repair, but because they can substitute for it. Talk is cheap. But repair is risky. It costs time and money. Plus, solutions don’t always work according to plan, so it could also cost credibility. It’s easier just to apologize and leave it at that. In places that reward visibility over outcomes, it makes sense to favour apologies in place of repair because they convey moral alignment with no material obligation.

Make no mistake. Normalizing apologies without the willingness to repair has long-term consequences for everyone. We’re not talking about apologizing for small slip-ups. Sure, if you bump into me on the street, I won’t ask for compensation. I wouldn’t even expect it.

But when apologies are made for some other person or group of people, living or dead, having committed the worst atrocities, the gap between speech and repair becomes impossible to ignore. If there’s never a remedy to the problem after the apology, then over time, we internalize the idea that an apology is good enough. Speakers and audiences learn that acknowledgment alone discharges responsibility. The moral ledger is closed with words instead of work.

If the world is as broken as some claim, and societal leaders apologize for it but never repair it, then, of course, nothing ever improves. This isn’t necessarily because those leaders are bad people. It’s because we live with incentive structures that reward the appearance of accountability while discouraging the real thing.

It’s said that “saying sorry is the hardest part.” But saying sorry is only hard when it commits you to something you can’t yet measure or control. When you know you have to make amends and you don’t know how much you’ll have to sacrifice for it.

That uncertainty is what’s terrifying.

It’s not so much shame as it is fear of what’s coming that makes a sincerely remorseful person bow one’s head in apology. When politicians bow their heads to act remorseful or when slactivists post apologies on behalf of others on social media, we can tell that’s just theatre. Because none of them are bound to any obligation to fix anything.

The Value of Apologies

So, if we want a good life, healthy relationships, and a robust, strong society, we need to remind ourselves that an apology isn’t the first step to making amends. Or the only step. In fact, there are three steps to take:

Recognition

Acknowledgment

Repair

Remorse emerges from the recognition that we did something that negatively affected someone else. Often, recognition requires conscious reflection.

An apology is just the acknowledgement to the affected person that we feel remorse for what we did, and we’d like to make amends.

It’s the remorse from the recognition that drives the willingness to repair, which is key to what makes a sincere apology hard. Because then the apology doubles as an I.O.U. You’re saying, “I’m willing to pay an unknown price to make it right.”

That’s also why without remorse and a desire to repair; an apology is just theatre. That’s why corporate and political apologies are too often empty and pointless.

An apology is not the first step to repair.

The first step toward repair happens in silence.

Reply to belowthesurfacetop@gmail.com if you have questions or comments. I’d love the hear from you.

Excessive apologizing also makes each apology less meaningful. This ties into the importance of exercising restraint, which I explore more in Dive 110 for those of you who want to learn how to make apologies more impactful.

I also dive into when activism becomes a grift in Dive 109:

Thank you for reading. Apologize Authentically. And I’ll see you in the next one.