Dive 78: Trust the Experts? But who’s the expert?

On separating experts from “experts.”

Hey, it’s Alvin!

In 2008, a lawyer hired me as an ergonomic expert to investigate a car accident in mid-town Toronto, Canada.

When most people hear “ergonomics,” they think about $1000 office chairs. The ones that better support the lumbar of your spine to keep a healthy sitting posture… when they’re adjusted correctly.

Ergonomics is more broadly about applying psychology and physiology to technological design. Also known as human factors, the goal is to have people use technology more safely and efficiently. That’s why ergonomists are sometimes consulted when there’s an accident where human error could have played a role.

In 2008, I and 3 other ergonomics experts went to analyze the accident site on behalf of the defendant. The plaintiff was driving south down a main road. And the defendant was exiting a driveway, turning left, southbound, onto the main road when they collided. We saw a few factors that could have affected the defendant’s ability to see conflicting traffic as he exited the driveway:

There was a building to his right that could have obstructed his view.

He had to cross northbound lanes to head southbound, which meant he could have been distracted by northbound traffic.

He also had to look out for jaywalking pedestrians.

The defendant would have faced west on a late autumn afternoon. The sun would’ve been low on the horizon, which could’ve affected his vision.

With that, we brought our analyses to court for the trial.

I don’t remember the result of the trial.

I didn’t care because it was a mock trial. Everything I described above was part of a class I took in a course called Case Studies in Ergonomics. My classmates and I did go to the former site of a car accident that happened years ago for a site analysis. The goal was to practice applying ergonomic theories to a real-world scenario. Along the way, I learned that not anyone can just call themselves an “expert” in the court of law.

What surprised me at the time was how rigorous the legal process is when introducing an expert witness into a court case. If a lawyer wants to onboard you as an expert, they’re going to vet you thoroughly. It makes sense. They want to make sure you have the knowledge, experience, and qualifications to comment on a specific aspect of a case. They need you to comment on it confidently because their job is to advocate fiercely for their client.

You’ll also be cross-examined by opposing counsel. So, you better be able to keep your cool when you’re finally on the stand where the opposition challenges your qualifications and your analyses.

Of course, experts don’t just exist to serve the court of law. But a public “expert” isn’t quite the same as an “expert witness.” I’ll explain why in a bit.

What got me thinking about experts is the recent rumblings about “misinformation,” and “disinformation.” Lies. The government, the media, and major online platforms all want us to be better informed for our safety. So, we’re told. And one of the most common suggestions I hear on how to “combat misinformation” is to consult experts.

“Trust the experts.”

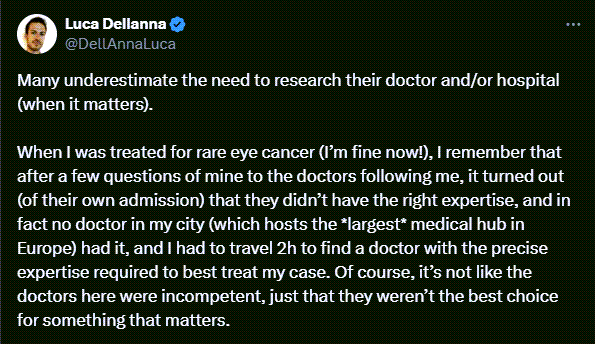

I’m wary about this advice. You should be too. Because my experiences working with experts and AS an “expert” showed me how dangerous it is to obey experts mindlessly.

For one, experts are humans. Humans can lie. So, experts can lie. It’s harder in court because lying in court is a crime. But it’s relatively easier in public.

Even honest, well-intentioned experts can be wrong. Maybe they made mistakes in their analyses. Do they publicize their work so anybody can review it? Maybe they couldn’t see the situation from other perspectives. What if they just lack experience?

Even honest experts may not be truthful. There’s a difference between honesty and truth. In the words of Matthew Frederick,

“Being honest means not telling lies. Being truthful means actively making known all the full truth of a matter.”

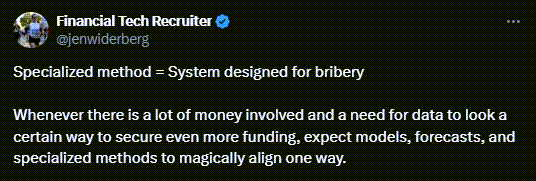

An expert doesn’t have to lie. But they also don’t have to tell the full truth of a matter in public. Some call this “lying by omission.” Especially when they’re paid to present only one side of a matter. Or if they want to push a specific perspective.

A key difference between an expert in court and an expert in public is that the former must be truthful. But even so, they can still be wrong.

The only reason we ever need to “trust the expert” is because we lack expertise in a subject. But if we lack expertise, then how can we judge an expert by their expertise? We can’t. Which means we also can’t tell whether an expert is trustworthy based on what they’re telling us.

So how can we best protect ourselves when someone presents an “expert” (or as an expert) that “we should all listen to?”

Be a Fierce Opposition

The problem with this scenario is that there’s no “opposing counsel.” When we’re presented with just one side of an issue and no one’s representing the opposition, then WE must be both…

The fierce opposition, AND

The judge

These are two separate roles. And a person responsible for protecting their own interests must be both. Because we don’t want to accept or reject what a person has to say without giving them a chance. What does it mean to be a fierce opposition?

Question their qualifications.

What qualifies them to speak on the topic?

What certifications and experiences do they have and NOT have (compared to other experts)?

Do they have “skin in the game”? What consequences do they face if they’re wrong?

Understand, then question their reasoning.

Are there inconsistencies in what they’re saying?

Are they answering questions directly and clearly?

Are there relevant questions they can’t answer and why?

Once you have the facts for and against the expert’s position, then you can be the judge of what to believe or not believe.

Use the Auto shop Approach

Another effective way of teasing out the truth of a matter is to find a common thread among multiple, independent sources. This used to be required for journalism and news reporting. It’s a lesson I learned from my father when I was young. And I like to call it the Auto shop Approach.

My father is no expert on cars. But like all car owners, he has to take his car to an auto shop for maintenance and tune-ups occasionally. He doesn’t just go to one auto shop, though. He goes to several.

At each auto shop, the maintenance worker would give my dad a list of items that needed fixing. He’d jot down the list and move on to another auto shop where he’d get another list of parts that needed fixing. My dad would do this a few times. Then he’d compare the lists. Because he can be confident that the item(s) common to all lists is an item that definitely needed fixing.

Of course, this only works if all the auto shops operate independently of one another.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t trust big tech companies who employ “experts” to filter out “misinformation” behind the scenes. To me, that sounds deviously dystopian.

Because then there’s no way for the rest of us to vet the experts they have. There’s no fierce opposition. And there’s no way to verify that their experts are operating independently of one another. Because they probably aren’t if they’re working for the same organization.

And if an organization can’t be transparent on how they’re filtering out “misinformation,” then they must be hiding something. What do they have to hide if it’s all for our own good?

We’re entering an age where we need to think independently and critically more than ever if we’re to make sense of the world around us.

Be a fierce opposition.

Be an impartial judge.

Especially when no one else will.

Reply to belowthesurfacetop@gmail.com or click ‘Message Alvin’ below if you have questions or comments. I’d love the hear from you.

Thank you for reading. Vet your experts. And I’ll see you in the next one.