Dive 117: The Case for Subtlety in a World of Overstimulation

Hey, it’s Alvin!

Have you ever tried a snack you enjoyed when you were younger only to find it tastes awful now?

I recently tried a small can of “original-flavoured” Pringles. I swear they used to taste more like potato chips. But now I wonder if they were always made of cardboard.

I remember snacking on junk food loaded with artificial colours and flavours marketed to kids, like:

Fruit roll-ups

Fruit by the foot

Fruit gushers

Starburst fruit chews…

As you can tell, I loved fruit…

…flavoured candies. And Oreos. But it’s been so many years since I had an Oreo. So, when I saw a pack in a store, I had to buy it for the nostalgia and… research…

It’s way sweeter than I remembered. The icing wasn’t as creamy. And the cookie didn’t match the “chocolate” profile in my memory. It turns out cookie manufacturers adjust recipes from time to time, and our memories are fallible. I don’t hate them. At least they didn’t taste like cardboard. But I also don’t crave them the way I used to, and I’m at peace with that. More than anything, this “experiment” showed…

Sustained intense flavours can dull our senses for subtlety.

On the surface, it’s like, “What’s the big deal?” But I also realized…

Subtlety is vital to our well-being and even survival.

When I say, “intense flavours,” I’m not just talking about food. Any sustained, intense environmental stimulus can dull our sense of subtlety. But let’s focus on food for now.

Flavour Blasted Flavours

There’s a study that shows that those on a low-sugar diet find moderately sweet foods sweeter than those on a regular diet. Not only that, but “blocking sweet taste perception promotes the consumption of more sweet foods.”

We also know that we become less sensitive to a stimulus after constant exposure to it. Psychologists call this sensory adaptation. So, the more we expose ourselves to intense flavours, the more we dull our tastebuds to subtle flavours. This has health implications because natural, whole foods often have subtle flavour profiles. For example,

The sweetness of fresh mozzarella.

The fragrance of a juicy Ambrosia apple.

The hint of bergamot in a cup of Earl Grey tea.

And even the stale cardboard of potato chips. I’m sorry, but I really am disappointed with those chips.

When a person snacks on Takis all the time, their sense of taste would be so accustomed to intense flavours that they would struggle to detect subtler flavours of natural, whole foods. The healthier foods would taste bland by comparison, pushing this person towards sweeter, saltier, fattier junk foods. After all, if you compare the flavour intensity of an orange-flavoured candy to an actual orange, the candy is designed to kick the orange’s ass.

If oranges had asses. And if candies had feet.

There are other reasons a taste for subtlety is vital to our well-being and survival. Being able to detect subtle changes in food quality means you’re more likely to catch food going bad. Or food that was tampered with.

Better yet, a taste for subtle flavours makes life’s little moments more memorable because it requires you to be present in the moment. As chef Jim Sevier says, “learning to taste is also about developing a heightened awareness of our senses, as we explore the vast spectrum of flavors and expand our palate with every bite.”

But this isn’t just about food. Sensory adaptation happens with all environmental stimuli. Like sound.

Turn down for what?

Today, 1 in 5 teens experience hearing loss, which is 30% higher than 20 years ago. It’s partly because more teens today wear headphones. So, they’re more exposed to intense sound volumes for longer periods. Excessive noise levels damage tiny hair cells in the inner ear that cannot regenerate, impairing the ability to hear.

While this is more physical than psychological, the effect is the same. The more we expose ourselves to loud noises, the more we lose our ability to hear quieter, subtler sounds.

This is even more disappointing, for all the talk about how today’s youngest are more stressed than ever. Because it is often the quietest, subtlest sounds that are the most calming and relaxing.

The birds chirping among the rustling leaves of a maple tree.

The light summer breeze brushing against the ears.

The flow of a river in the middle of the woods.

But the greatest stressor might be one of the least subtle assaults on our senses that exists in the modern era.

Attack on Psyche

Modern mass media has no concept of subtlety.

News media and social media producers are so desperate for attention, they can’t help but punch you in the face with over-sensational headlines and posts.

It’s not just that there are people who don’t read the bodies of articles. They might. But my theory is that a sensational headline can blunt a person’s ability to detect subtle nuances in the body that might even contradict the headline. Sensory adaptation strikes again. There are two psychological effects that combine to attack the reader:

The priming effect describes how the headline sets the tone and angle that the following body would be read.

And cognitive overload is used by the headline to overwhelm the reader with emotion, making it harder for the reader to process information beyond what the headline conveyed. Not unlike cooks in the medieval times, who used “heavy stews and pungent sauces” to mask the smell and taste of rotting meat.

The combined effect makes it hard for readers to detect nuances that may mellow, or even contradict, the message delivered by the title. The over-sensational title mutes our ability to detect subtle contradictions in the body. It’s like Homer Simpson coating his tongue in candle wax to mute his taste buds so he could swallow hot chilli pepper.

This would also explain why some readers are less affected.

Because if you know how the game is played, you can train yourself to ignore the headline to focus on the content. But not everyone can do that.

I’m not suggesting that journalists should be more subtle. The news should be explicit because it’s reporting on events that can affect readers materially. But then the news should report on all sides with the same gusto. Like they used to.

The Importance of Being Subtle

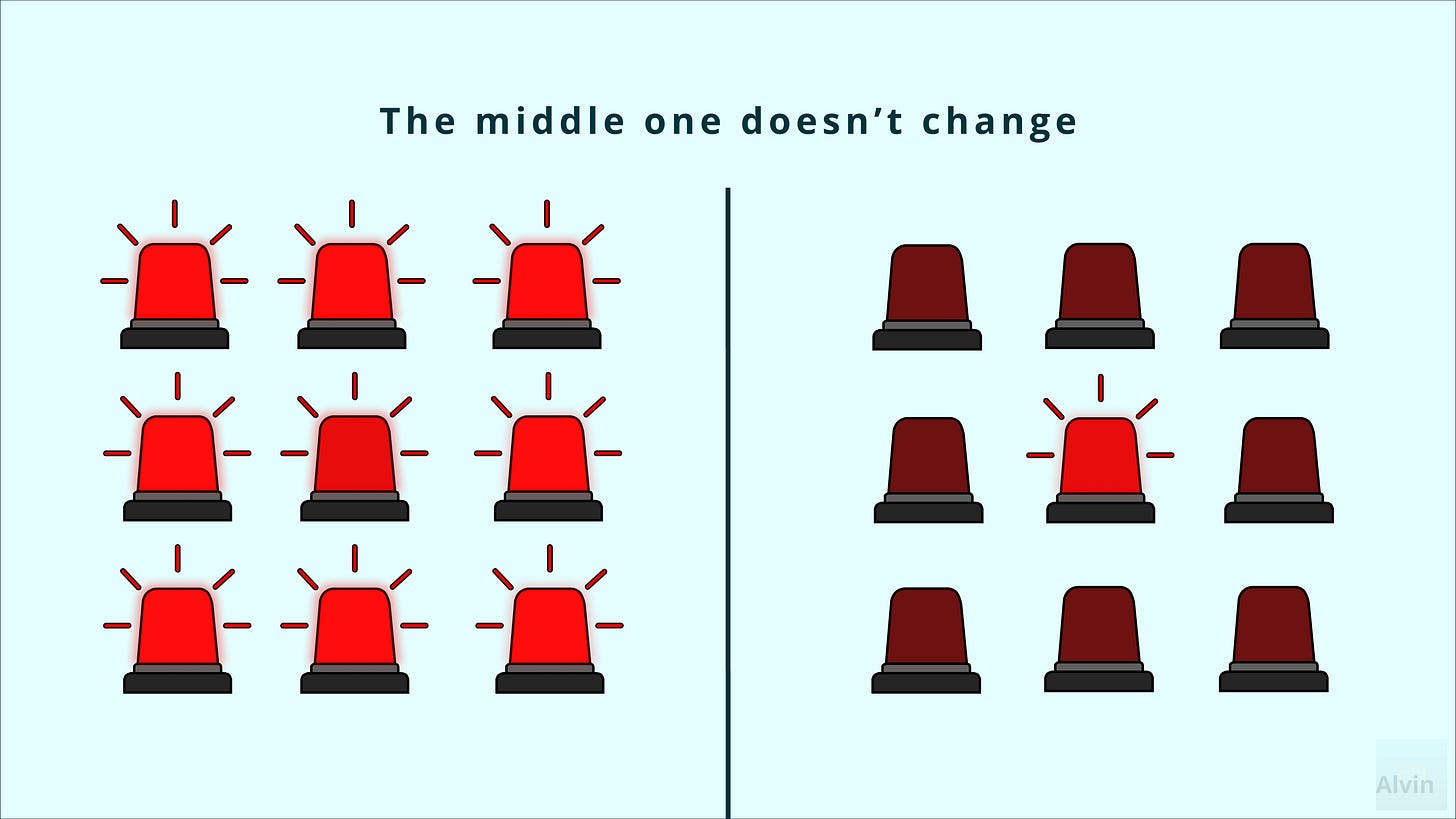

It helps to be aware when our taste for subtlety is being blunted.

Because a taste for subtlety is crucial for our well-being and survival.

Because it allows us to detect subtle changes in our environment that may signal something that deserves our attention—something best addressed sooner rather than later.

The cost of excessively eating extremely flavoured corn chips, or even Oreos, isn’t just the obvious lack of nutrition. Or anti-nutrition. They dull our taste for subtlety to where veggies aren’t just underappreciated; they’re hated.

If nothing else, the ability to detect subtlety lets you relax and enjoy little, peaceful moments of everyday life.

Embrace the subtle.

Reply to belowthesurfacetop@gmail.com if you have questions or comments. I’d love the hear from you. Practicing restraint helps in embracing subtlety. I wrote about restraint and how it promotes gratitude in Dive 110. Be sure to check it out:

Thank you for reading. Develop the taste for subtlety. And I’ll see you in the next one.